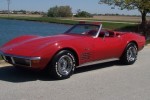

This summer, we are talking “Generations”. Every week we’ve highlighted another Generation of Corvette. We have pictures, videos, and some great reading material on each Generation of Corvette. In this post, we look at the C3.

Barely five years elapsed between the introduction of the ’63 Sting Ray and the close of the C2 generation in the ’67 model year, and during that time the Corvette stayed on a track of steady improvement that resulted in a world-class sports car. Things would be different in the Vette’s third go-around. Not only was it the longest, at 15 years, but this Corvette generation had to weather a turbulent era that made it tough to hold on to its top-echelon status.

The Shark is Born

The sleek lines Larry Shinoda penned for the Mako Shark II concept car provided clear inspiration for the next iteration of the Corvette — as well as the generation’s “shark” nickname — but turning concept into reality wasn’t easy. The Mako’s styling cues, particularly its tall fenders and upswept tail, made for a sexy show car, but not one that was easy to live with — or see out of. So Shinoda and his designers worked on making the Mako more livable, while Zora Arkus-Duntov, the Corvette’s chief engineer, figured out how to fit the Vette’s mechanicals within the new body envelope. Under the new skin the Corvette was essentially a carryover from the C2’s later years — same 98-inch wheelbase, chassis layout, and engine choices — but the Mako Shark’s front-end styling didn’t allow for much airflow to the engine. The front air grilles were opened up, while an air dam was added under the car to help direct flow to the radiator. Front fender vents proved to be more than decoration and actually let hot air escape from the engine bay.

The previous IRS design was incorporated into the new car, but the front suspension was revised to help keep the tires planted under hard acceleration. The standard Rally wheels grew in width to 7 inches, allowing for big F70-15 meats at all four corners.

In addition to cutting down the Mako’s tall fender bulges, Shinoda’s team also replaced the show car’s dramatically styled boattail rear end with a vertical back window recessed between two buttresses. Initially the car had a lift-off, Targa-style roof, but without the reinforcement of a fixed panel, the body flexed too much. So instead, a strut was positioned between the windshield and the B-pillar arch, and removable roof sections flanked that strut, forming the Vette’s T-tops.

The new Vette’s interior was completely revised. The instrument panel now had a big speedometer and tach in front of the driver and a raft of other monitors in the center console. “Astro” ventilation — which drew fresh air from the cowl and exhausted it via vents behind the back window — was new, as was the removable back window. As was the case in ’67, engine options ranged from a 300hp 327 to the mighty L88. One big powertrain change was the addition of the three-speed Turbo-Hydramatic automatic transmission, which replaced the long-in-the-tooth Powerglide.

Reportedly, early customers weren’t happy with the quality of the fiberglass bodywork on the new ’68 Corvette, but that didn’t stop Chevrolet from selling 28,566 of them, a significant lift from the 22,940 ’67s sold. From a sales standpoint the Corvette would just get hotter and hotter, even if its performance parameters would soon suffer.

Chrome Bumpers

While the shark generation of Vettes lasted a long 15 years, the car’s look was refreshed every five years, neatly breaking the C3s into three different sub-generations. The early C3s, the ’68-’72 models, are distinguished by their chrome front and rear bumpers. Spotting the differences between those first five years gets a little trickier. The ’68s, for example, did not wear the Stingray name, but the ’69s did, and now the beast was spelled as one word, not two. Side exhausts were a one-year-only option in ’69, as was bright trim for the fender louvers. The door buttons used in ’68 were gone by ’69, and the backup lights moved into the inboard taillights. For the ’70 model year (which was cut short by strikes and is often labeled ’70-1/2), the front grilles and the fender louvers were redesigned with egg-crate patterns, the wheel openings were flared at the back, and the exhaust tips went from round to rectangular. That body style remained unchanged for the ’71 and ’72 model years.

There were more dramatic changes taking place underhood. The muscle-car era essentially peaked and then died between 1969 and 1972, and the Corvette’s powertrain options mirrored those highs and lows. In ’69 the base engine was enlarged from 327 to 350 cubic inches (though the 300hp rating remained the same); while at the other end of the engine spectrum, the all-aluminum, 427-inch ZL1 engine was added to the options list. Like the L88 the ZL1 was intended for racing use only, and like the L88 the ZL1’s output was laughably underrated by GM brass at 430 hp. Two new engines appeared for the ’70-1/2 model year. Though the L88 and ZL1 were no longer available, the more garden-variety Mark IV big-block was stroked from 427 to 454 cubic inches, creating the LS5. Its 390hp rating was the same as the L36 427, but peak torque jumped from 460 lb-ft to 500. (A second optional big-block, the LS7, was mentioned in some dealer literature and featured in a couple of magazine road tests but never made it into production.)

A significant new small-block also came on the scene. Called the LT-1, it was an evolution of the 302ci small-block Chevy used for Trans-Am racing. With a solid-lifter cam, big valves in the heads, and 11:1 compression, the LT-1 pumped out 370 hp in the Corvette and 380 lb-ft of torque, and yet delivered those numbers in a package far lighter than big-inch motors offering similar output. Less weight over the nose, of course, meant a better-handling Vette.

Sadly, ’70 would be the pinnacle powertrain year. Big-block buyers could still get a serious stump puller when the 425hp LS6 big-block was made available in Corvettes for ’71, but otherwise, compression ratios were cut in a corporate-wide edict to reduce emissions. The LT-1 went from 350 hp to 330 in ’71, the LS5 from 390 to 365. And that was just the beginning. In the ’72 model year it looked like every manufacturer’s power numbers fell off a cliff, as the industry went from “gross” to “net” power ratings. The Vette’s standard 300hp 350 was now rated at 200 hp, the LT-1 dropped to 255, and the LS5 to 270 hp. Yet despite the decline in power, and despite the car’s rising price — a coupe cost more than $5,000 for the first time in ’70 — Corvette sales remained strong. And they would grow again with the ’73’s mid-cycle redesign.

Soft Bumpers

Federal regulations mandated that all ’73 model cars be fitted with bumpers that could withstand a 5-mph impact. So the Corvette’s chrome bumpers were replaced with soft, body-colored urethane units. For ’73 the nose received the soft-bumper treatment; by ’74 both ends of the car had the energy-absorbing systems. That makes the ’73 models the only ones with soft front and metal rear bumpers. The new bumper lengthened the car overall by 2 to 3 inches, but it added less than 40 pounds to the Vette’s overall weight. The new nose also allowed the Corvette’s designers to render a new hood, one that drew cold air into the engine via cowl induction and also got rid of the doors that hid the windshield wipers. And though not related to the new hood or crash standards, the ’73 Vette also lost the previous models’ removable rear window.

The new rear-bumper design was the only styling difference between ’73 and ’74 models; for ’75 the styling was also carried over, though the rear bumper cover became a single piece rather than two, and the convertible body style disappeared — for a while, at least. In ’76 the cowl-induction hood was replaced with a more conventional hood, and there were two different “Corvette” treatments on the rear bumper cover, with letters that were recessed and letters that weren’t. This also marked the last appearance of the Stingray fender badges. In the final year of this Vette iteration, Chevy’s stylists put a new crossed-flag emblem on the car’s nose and blacked out the A-pillars.

Beneath the skin changes were many, and few were good. For the ’73 model year, engine choices were down to three: the 190hp base L48 small-block, the 250hp L82 small-block, and the 275hp LS5 454. The L48’s output rose by 5 hp in ’74, but that was the final year of the 454 option; by ’75 the L48 was rated at a dismal 165 hp, and the L82 dipped to 205 hp, thanks to the addition of catalytic converters. The ’75 model year marked another milestone: the retirement of Zora Arkus-Duntov. The man known as the “father of the Corvette” handed the reins to Dave McLellan, who had been with GM since 1959 and worked closely with Duntov during the final six months of his tenure. As if to reassure Duntov that the Corvette could soldier on, output grew just a bit in ’76, with the base engine making 180 hp and the L82 210. Those numbers would hold through ’77 as well.

Fastback

The ’78 model year marked the Corvette’s 25th anniversary, and Chevrolet made some significant changes to take the shark into its final five years of production. Most obvious was the new fastback-styled back window, which both increased rearward visibility and made more room inside the car (though adding hinges to that fastback to ease cargo loading wouldn’t happen for a few more years). All ’78 models received 25th anniversary badges; some buyers opted for the special Silver Anniversary paint scheme, a two-tone job with dark-silver panels under a lighter-silver upper body. This year also marked the first time a Corvette was used as the pace car for the Indianapolis 500, and a limited run of pace-car replicas was built to commemorate the event. Well, sort of limited. Though initial plans were to make just 300 of the Limited Edition models, eventually more than 6,500 were produced, dashing the hopes of many who thought they had an instant collectible on their hands. The ’79 model’s styling carried over from ’78, but in the ’80 model year, Chevy’s designers shook things up a bit by restyling the front and rear bumper covers, giving the car a more aggressive look, and returning the ducktail spoiler to the car’s rear end.

There were no styling changes to speak of for ’81, but the year marked a huge shift for Chevrolet, as Corvette production moved from St. Louis to Bowling Green, Kentucky. The new assembly plant would be solely dedicated to the Corvette, allowing an increase in manufacturing rates, better build quality, and new painting processes (the single-stage lacquer used in St. Louis gave way to two-stage enamel in Bowling Green). It also set the stage for production of the C4, though that wouldn’t happen as early as planned. Tasked with keeping the current Corvette fresh while developing the next-generation model at the same time, McLellan issued a new limited-edition model in ’82, the Collector Edition. It finally offered a hinged version of the fastback glass window, plus special paint, turbine-style wheels, and leather upholstery that matched the exclusive paint color outside. It notched another Corvette milestone, too–the first Vette to retail for more than $20,000.

Yet the ’82 Corvette was home to some significant engineering developments as well. From a powertrain standpoint these final shark years were pretty depressing, with engine offerings hovering around the 180-230hp range (and California customers having to make do with even less, thanks to the state’s restrictive smog laws). But McLellan was eager to show off some of the technology destined for the C4 Corvette, so the ’82 model was home to a 350-inch small-block equipped with the first “Cross-Fire” fuel-injection system. Cross-Fire mounted two throttle-body fuel injectors on an intake manifold that looked a lot like the cross-ram intakes used on the Trans-Am Camaros. Trick as it looked, the L83 small-block was good for just 200 hp, a 10hp increase over the ’81 L81 motor. Backing the new engine was a new automatic transmission, the first 700-R4 four-speed. It was the sole transmission available in ’82, the first time since ’54 that a Corvette could be ordered with an automatic only. McLellan had more — much more — up his sleeve with the planned introduction of the fourth-generation Corvette in 1983. But just as fans of the Mako Shark II had to wait for the production version to arrive, the C4 would prove to be tardy, too.

Content (except pictures and video): Motor Trend